Case in point: last week’s rate-hike blitz. This all implies a clear sequence: overtighten policy first, significant economic damage second and then signs of inflation easing only many months later. We’re tactically underweight developed market (DM) stocks and prefer credit.

Rapid rate rises

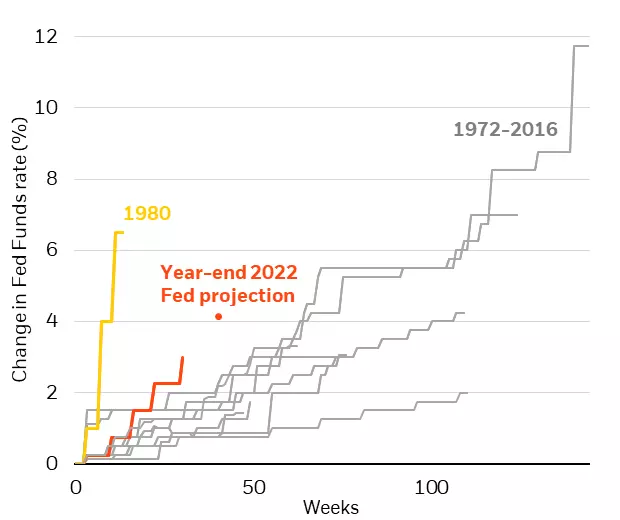

U.S. interest rate tightening cycles, 1972-2022

Sources: BlackRock Investment Institute, with data from Refinitiv Datastream, September 2022. Notes: The chart shows the speed of Federal Reserve hiking cycles since 1972. The yellow line shows the fastest cycle. The orange line shows the current cycle. The orange dot is the projected change in the fed funds by year-end 2022 since the start of the cycle.

The Federal Reserve is on its fastest rate hiking cycle since the early 1980s (see orange and yellow lines in chart). It hiked another 0.75% last week and projected rates would go even higher. The Fed now sees the fed funds rate rising to 4.6% by the end of 2023, a significant bump from prior views. The problem? Updated economic forecasts are too optimistic, in our view. The Fed still sees positive growth this year and sees it picking up next year. But it also wants to see evidence core inflation is on a decisive 2% trajectory beyond 2023 before it stops hiking. This soft landing doesn’t add up to us. We think quashing inflation that quickly amid constrained production capacity would take a recession – a roughly 2% hit to economic activity and 3 million more unemployed. We think the Fed is not only underestimating the recession needed but ignoring that it’s logically necessary.

Why would a recession be needed to reduce core inflation? Unusually low supply can’t meet demand. That’s driving inflation. There are two reasons why. First, a labour shortage – people who left the workforce during the pandemic haven’t returned yet. Second, the economy wasn’t set up to match consumer spending’s massive shift from services to goods that hasn’t fully reversed even as the world moves on from the pandemic. Central banks can’t fix these constraints, in our view, hence a brutal trade-off: trigger a deep recession by hiking rates or live with more persistent inflation. The Fed’s forecasts don’t acknowledge this trade-off. It reconciles this by assuming production constraints will rapidly dissolve, causing inflation to fall quickly. But if that’s the outcome, what’s the point of the fastest hiking cycle since former Fed Chair Paul Volcker’s era?

The case of the UK

The Bank of England (BoE) has been transparent that quickly pushing inflation down will require a recession. But the UK now faces different challenges that change fundamentally how we look at UK assets. The UK government revealed a fiscal splurge on Friday that effectively throws money at an inflation problem, in our view. After last week’s hike, this means the BoE will have to hike more and leave rates elevated for longer than it planned to, we think. But more importantly, the fiscal splurge puts the UK’s fiscal credibility into question. The plans follow measures to subsidize energy bills and amount overall to 10% of GDP over the next five years, we estimate. The pound cratered to a 37-year low against the dollar and gilt yields surged after the news. All of this will help motivate the BoE’s hawkishness. That’s why we’ve downgraded UK gilts to underweight.

Central bank implications

The implications of all of this: We think central banks will keep raising rates until it’s clear that core inflation is coming down. That means economic activity is set to fall across DMs. The Fed’s current policy may drag down U.S. growth far more than it realizes. In Europe, we see the European Central Bank’s resolve to push inflation down fraying as it wakes up to the bleak outlook. But that reaction will come too late to prevent the central bank from amplifying the energy shock’s recessionary forces, in our view. The continent will see a deeper recession than in the U.S.

Our bottom line

We’re tactically underweight DM equities as stocks aren’t fully pricing in recession risks. We don’t see a “soft landing” outcome where inflation returns to target quickly without crushing activity. That means more volatility and pressure on risk assets, we think. We prefer investment grade credit as yields better compensate for default risk. Plus, high-quality credit can weather a recession better than stocks. We find inflation-linked bonds more attractive and stay cautious on long-term nominal government bonds amid persistent inflation.

Market backdrop

Stocks slid and yields surged after hawkish central bank actions. The Fed raised rate expectations into next year and revised growth and unemployment forecasts. We think they’re too optimistic. The Bank of England also hiked. But a fiscal splurge may lead to even more hikes and poses risks of further rises in long-term yields and pound depreciation. Japan intervened for the first time since 1998 to prop up the yen. Bucking the trend, the Bank of Japan kept its yield curve control policy.

We’re watching inflation data in the U.S. and the euro area, including the Fed’s preferred PCE metric. For now, the Fed only seems to care about evidence inflation is decisively on a path toward its 2% target. The assessment of U.S. consumers will show if they agree with Fed forecasts that the economy can avoid recession. We think the Fed is underappreciating the economic damage needed to bring inflation down quickly to target. We see persistent inflation and recession next year in the U.S.